Ethical and sustainable investment

Follow the money: Why meat and plastic are the new coal

July 2021

Approximately 4 minutes

Usually, when people follow the so-called smart money in the world of stocks and shares, they look to see where it is going — what is being bought, by way of investment.

When it comes to environmental and ethical concerns, however, it is equally important to identify areas where money is leaving — what is getting sold off, as a form of 'divestment'.

Divestment is the name given to the practice of reducing financial commitments, or even disposing of assets completely. Often, it happens in response to sustainability questions raised around environmental impacts or ethical issues, such as pollution, or human rights.

Driven by declarations of a climate emergency worldwide, the most conspicuous example of divestment at present concerns movement of money out of fossil-fuel stocks, especially coal. The fossil-free community comprises tens of thousands of institutions and individuals, plus totals that run into trillions of dollars.

Who is joining the divestment movement?

Educational establishments have been in the vanguard of the fossil-fuel divestment movement, and, in many cases, their cultural leverage is as powerful as their assets are substantial. Whether you are talking about the global branding of Oxford University, or the $126 billion portfolio of the University of California, profile is important.

Funds representing faith-based organisations, such as the Church of England, have also quit fossil fuels; as have regional and local governments, including New York City and Maine, which just became the first State in the US to pass divestment legislation.

In the finance and investment community, the global growth of environmental, social and governance (ESG) funds is really gathering pace, with divestment part of that picture.

The list of asset managers leaving coal is long and growing, plus key public statements made by BlackRock, the world's biggest investor, were seen as something of a milestone.

Divestment from fossil fuels such as coal has been driven by a combination of factors, including global climate goals and national carbon targets, shareholder activism and consumer pressure. Crucially, there was also somewhere attractive for the money to go as an alternative — heading away from 'dirty' energy stocks into clean tech and green power.

This is a pattern starting to repeat itself in other markets and sectors.

Meat off the menu

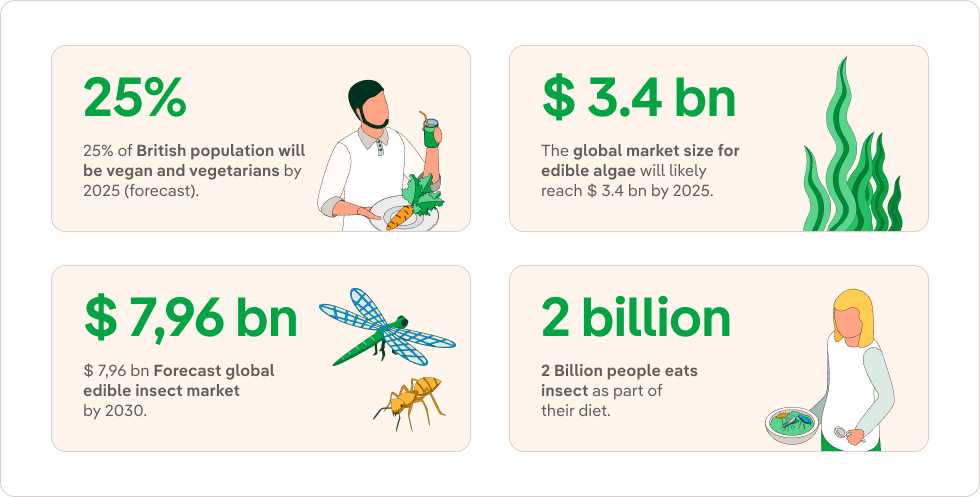

As evidenced by figures for Veganuary — where nearly one new person joined up every three seconds in 2021 — consumers are sending strong signals to the market that meat is increasingly off the menu for Millennials and investors, even pet food.

In truth, investment in meat had been under pressure for some time on sustainability grounds, pre-Covid — with questions around animal welfare, land use and deforestation, methane emissions and hidden costs of grain-feed production.

In response, funders are making initial moves away, with Nordea Asset Management divesting $45 million from the world's top meat producer, Brazil-based JBS, over unanswered questions about Amazon deforestation.

As for alternatives, there is a feast of tasty options on the investment menu for meat-free money. High-profile disrupters like plant-based pioneers Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat have their burgers served in Burger King and McDonald's, respectively. Cultured, lab-grown, 'no-kill' substitutes for both the chicken and the egg are available from Eat Just.

Offering an animal friendly climate-conscious portfolio, Beyond Investing has established the US Vegan Climate Index. Furthermore, the fastest-growing investor network focused on ESG risks in the global food sector, the Farm Animal Investment Risk and Return (FAIRR) initiative last year surpassed $20 trillion in assets under management.

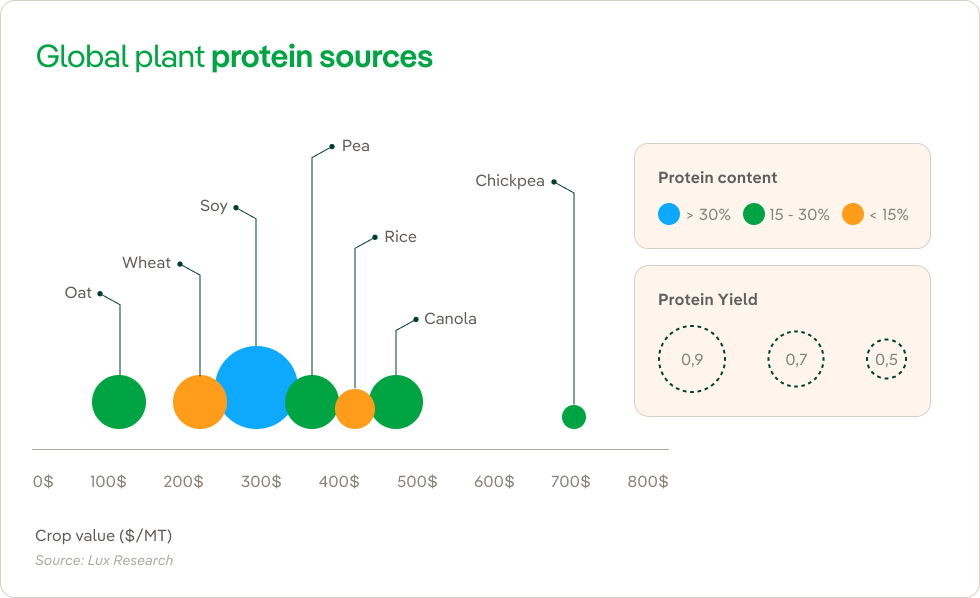

According to Lux Research, pea, canola and oat are the plant protein crops to watch, plus Barclays predicts big growth in edible bugs. Some two billion people already eat insects as part of their diet and the market could be worth almost $8 billion by 2030.

Plastic in the junk

In the case of plastic, there has been a wave of consumer anger and activism from the 'Blue Planet generation', who watched the shocking images on screen of ocean pollution and impacts on marine life. Almost three quarters of a million people have now signed the petition to get Amazon to offer plastic-free packaging options.

In addition, legislation is putting a regulatory squeeze on producers, particularly of single-use plastic. Carrier bags have been banned in various countries across Europe and, as of April next year, the UK will be bringing in a new £200-per-tonne Plastic Packaging Tax.

The business sector is duly responding, with five of the UK's biggest names in branded FMCG — Mars UK, Mondelez International, Nestlé, PepsiCo and Unilever — coming together to form the £1M Flexible Plastic Fund, led by producer compliance scheme, Ecosurety, with award-winning environmental charity and social enterprise, Hubbub.

There is also technical innovation happening, with the likes Toraphene, billed as the world's first fully biodegradable, compostable, commercially viable alternative to plastic.

In terms of following the money, though, the most telling indicator that plastic is potentially going down the same divestment path as fossil fuels is the emergence of plastic offsetting.

Following in the footprints of its carbon predecessor, plastic offsetting allows organisations to pay towards plastic recovery and removal undertaken by another party, so balancing the scales for the plastic impacts they are unable (or unwilling) to avoid.

With the Plastics for Change scheme, it costs $0.60 to purchase a 1kg offset of certified ocean-bound plastic removed. Potential offsetting applications for brands with plastic waste liabilities in such as the fashion industry even made the business pages of Vogue.

The 'new coal'

So, if a first step towards identifying further divestment trends is perhaps to find the right kind of problem — a cause that inspires policy shifts and consumer campaigns, one in which the stock market also has a significant stake — then factory-farmed meat and single-use plastic would appear to be prime candidates to become the 'new coal'.

Jim McClelland is a writer, editor and speaker, specialising in business and the built environment — from cities and climate to the circular economy. Ranked among the top three Media Influencers in Sustainability worldwide, Jim has also edited and contributed chapters for books on Unconventional Computing and Welfare Architecture. He is also a contributing author of the annual Circularity Gap Report, published every year at Davos.

Article published in issue 9 of Shapes in July 2021.